Playing with RISC-V

Over the past few years I’ve started to sour on x86 architecture for just about everything. From servers, desktop, and mobile, I’ve long wished we had architectures competing with x86 at the high end.

Fortunately, there are plenty of architectures out there. From ARM and ARM64, to MIPS, there are choices. There is one recent one that has been getting my attention lately, and I’ve thought it’s time to start diving in to it.

RISC-V

RISC-V (pronounced “Risk Five”) is a fairly new architecture that has some interesting ideas behind it that make it worth looking it. Originally designed at UC Berkeley, it is an open architecture with the goal of being applicable to a wide range of devices.

An open ISA that is available for commercial use is not unique, but it is rare. Contrast to ARM, if you want to make your own ARM CPU, you need to license the ISA from ARM Holdings Group, to the tune of millions of dollars. While “open” is not a direct benefit to developers, it does mean that a variety of companies that fabricate their own silicon are interested.

RISC-V is also designed for multiple device profiles. It supports 32-bit and 64-bit, and is broken down in to a set of extension instruction sets, plus the always available integer base set. The ISA also documents and reserves a 128-bit architecture.

This “base” integer instruction set is present on any RISC-V implementation. Often called “RV32I” for 32-bit, or “RV64I”, this instruction set consists of 47 instructions required to move memory, perform computations, and arithmetic.

As of writing, some of the designs of the RISC-V architecture are still under active development, while others are finalized. The RV64I and RV32I are complete, while RV128I is still open for changes. The RV64I and RV32I set guarantees 32 registers. For smaller implementations, there is RV32E which limits the register count to 16.

The extensions are are follows

- “M” extension instructions offer multiplication and division.

- “A” extension instructions offer atomic instructions.

- “C” extension instructions are a few compressed for smaller encoding.

- “F” extension instructions offer single-precision floating point.

- “D” extension instructions offer double-precision floating point.

- “Q” extension instructions offer quad-precision floating point.

- “L” extension instructions offer decimal floating point.

There are more than that, but these are the basic and complete extensions. A vendor may choose to implement any, or none, of these extensions. Most of these extensions can be emulated with the base Integer instructions using compiler replacements, save for the atomic instruction set.

A key aspect though is that the ISA leaves open guidance and design for allowing a vendor to implement their own extensions and describing how they would be encoded.

The extension set is not entirely meant to be pick and choose whatever. The RV32E base set was designed with only supporting the M, A, C extensions in mind, plus any additional extensions sets implemented on top of it.

Hardware

That all sounds swell. But what about actual hardware? Currently, there is not a lot of hardware out there. SiFive though, makes a board called the HiFive 1 which is a small board with an RV32IMAC capable processor.

Notably, it works with the Arduino Studio, so there is a plenty easy way to get started with that.

I however didn’t have a lot of interest in using it as a board to run code that I already knew, I wanted to learn the instruction set, which meant I wanted to write assembly and throw it at the board and see what it did.

I initially struggled doing this in WSL for some reason, the details of which I haven’t quite fully comprehended yet. After switching to MacOS, things went a lot smoother, since much of the documentation was for Linux and Unix-like systems.

I decided to start with a very simple program. Add two numbers.

.section .text

.globl _start

_start:

li t1, 42

li t2, 48

add t3, t1, t2

nop

li is “load immediate” which allows putting numbers in to registers

immediately. The t prefixed registers are temporary registers. A simple

compile might look something like this:

riscv32-unknown-elf-gcc example.S -nostdlib -o example.elf

This will produce a binary that is close to working but has a problem that took me a while to track down. The disassembly looks like this:

example.elf: file format elf32-littleriscv

Disassembly of section .text:

00010054 <_start>:

10054: 02a00313 li t1,42

10058: 03000393 li t2,48

1005c: 00730e33 add t3,t1,t2

10060: 0001 nop

Loading this on the HiFive 1 doesn’t work because it doesn’t load at the

correct address. Reading through the HiFive 1 ISA and their documentation, the

entry point must be at the address 0x20400000. Fortunately, the HiFive 1

comes with a GCC linker script that does all the right things. It handles

the start address as well as other memory layout concerns. After re-compiling

with their linker script:

riscv32-unknown-elf-gcc example.S -nostdlib -o example.elf -T link.lds

Re-dumping the assembly shows that _start appears in the correct location.

Loading the program can be done with openocd, which is included in the HiFive

software kit.

Starting it with the correct configuration:

openocd -f ~/.openocd/config/hifive1.cfg

I moved some files around to make things easier, but they should be easy enough to track down in their software kit.

Once openocd, I can use the included RISC-V GDB debugger to remotely debug it.

openocd will start a GDB server on localhost:3333. Firing up the RISC-V GDB,

like riscv32-unknown-elf-gdb ~/Projects/riscv/example.elf, I can run the

following commands to load the software and start debugging it.

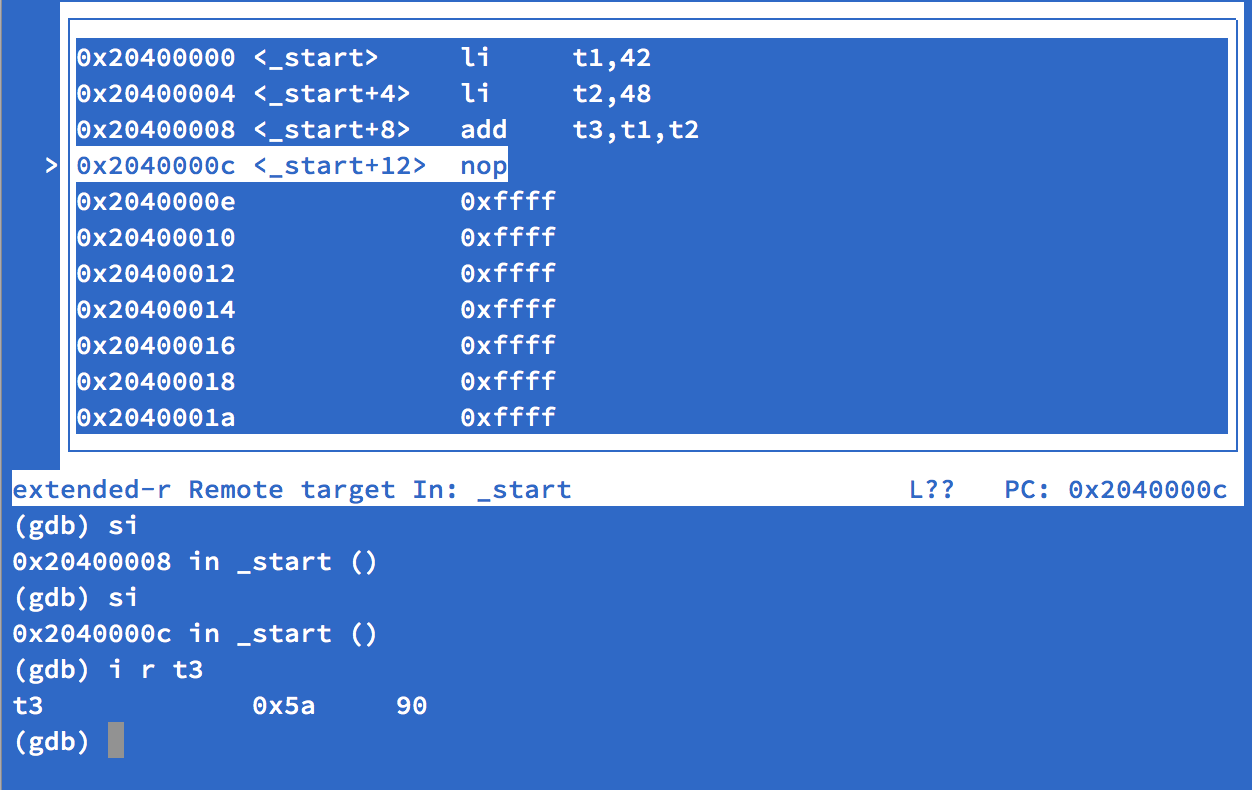

target extended-remote localhost:3333

monitor reset halt

monitor flash protect 0 64 last off

load

layout asm

and if all goes well, we get something like this:

Which is fairly exciting! Debugging my first RISC-V process, even if it does

something simple like addition. Performing a few stepi to step a few

instructions up to the nop, I can then use info register t3 (or just

i r t3 for short) we see we have 90 in the register, which the result of adding

42 and 48.

I’m hopeful that RISC-V will be competitive in the embedded and mobile CPU ISA space. It will take a very long time to get there, and even longer for less homogeneous environment like desktops and laptops, but I believe everyone will be better off if we simply had more to choose from. Even those that will firmly continue to use x86 would benefit from additional innovation and research into architecture design.

I’ll continue to play with RISC-V. If something interesting pops up, I’ll do my best to write about it.