NuGet Package Signing

Recently the NuGet team announced they were going to start supporting package signing.

The NuGet team announced that their solution would be based on x509, or PKI certificates from a traditional Certificate Authority. They haven’t announced much beyond that, but it’s likely to be just a plain Code Signing certificate with the Code Signing EKU. Certificates and PKI is not a perfect solution. Particularly, one of the problems around code signing certificates is the accessibility of them. Certificate Authorities typically charge for certificates and require identification.

This presents a problem to a few groups of people. Young people who are just getting in to software development may be excited to publish a NuGet package. However getting a code signing certificate may be out of their reach, for example for a 15 year old. I’m not clear how a CA would handle processing a certificate for a minor who may not have a ID. The same goes for individuals of lesser privileged countries. The median monthly income of Belarus, a country very dear to me, is $827. A few hundred dollars for a code signing certificate is not nothing to sneeze at. There are many groups of people that will struggle with obtaining a certificate.

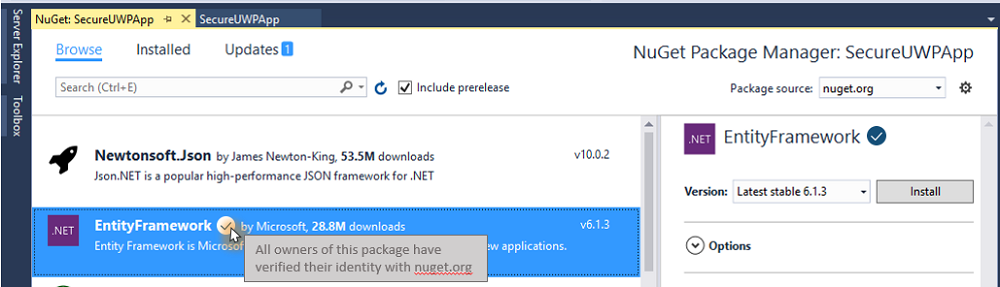

Not signing might be okay, with a few exceptions. The first being that the NuGet team described that there would be a visual indicator for signed packages.

This indicator is necessary for part of the NuGet team’s desire to indicate a level of trustworthiness. However, as a package consumer, the indicator will likely draw preference. This puts packages that are able to sign in a position of preference over unsigned packages. This also hurts the community as a whole; it’s simply better for everyone if as many packages as possible were signed.

Given that, the natural conclusion may be that x509 and PKI are not the correct solution. There are other options that will work, such as PGP and Web of Trust (WOT). Some members are asking the NuGet team to reconsider x509 and PKI. There are other issues with x509 and PKI, but the accessibility of code signing certificates seems to be the central point of the community’s concerns.

I am sympathetic to these concerns which I have also expressed myself previously. However despite that, I would like to now explain why I think the NuGet team made the right decision, and why the other options are less likely to be workable solutions.

PKI

x509 Code Signing certificates use Public Key Infrastructure, or PKI for short. The hardest part of signing anything with a key is not a technical problem. It is “Should I trust this key?”. Anyone in the world can make a certificate with a Common Name of “Kevin Jones” and sign something with it. How would you, the consumer of NuGet package signed by CN=Kevin Jones, know that the certificate belongs to Kevin Jones?

The PKI solution for that is to have the certificate for CN=Kevin Jones to be signed by someone you already trust, or in this case a Certificate Authority. The CA, since they are vouching for your certificate’s validity, will vet the application for the certificate. Even when I applied for a free Code Signing certificate (disclosure, Digicert gives free certs to MVPs, which I am grateful for), they still performed their verification procedures which involved a notarized document for my identification. CAs are motivated to do this correctly every time because if they prove to be untrustworthy, the CA is no longer trusted anymore. The CA’s own certificate will be removed or blacklisted from the root store, which operating systems maintain themselves, usually.

While this has problems and is not foolproof, it has been a system that has worked for quite a long time. x509 certificates are well understood and also serve as the same technology as HTTPS. There is significant buy in from individuals and businesses alike that are interested in the further advancement of x509. Such advancements might be improved cryptographic primitives, such as SHA256 a few years ago, to new things such as ed25519.

A certificate which is not signed by a CA, but rather signs itself, is said to a self-signed certificate. These certificates are not trusted unless they are explicitly trusted by the operating system for every computer which will use it.

A final option is an internal CA, or enterprise CA. This is a Certificate Authority that the operating system does not trust by default, but has been trusted through some kind of enterprise configuration (such as Group Policy or a master image). Enterprises choose to run their own private CA for many reasons.

Any of these options can be used to sign a NuGet package with x509. I’m not clear if the Microsoft NuGet repository will accept self signed packages or enterprise signed packages. However an enterprise will be able to consume a private NuGet feed that is signed by their enterprise CA.

This model allows for some nice scenarios, such trusting packages that are signed by a particular x509 certificate. This might be useful for an organization that wants to prevent NuGet packages from being installed that have not been vetted by the corporation yet, or preventing non-Microsoft packages from being installed.

Finally, x509 has not great, but at least reasonably well understood and decently documented tools. Let’s face it: NuGet and .NET Core are cross platform, but likely skew towards the Windows and Microsoft ecosystem at the moment. Windows, macOS, and Linux are all set up at this point to handle x509 certificates both from a platform perspective and from a tooling perspective.

PKI is vulnerable to a few problems. One that is of great concern is the “central-ness” of a handful of Certificate Authorities. The collapse of a CA would be very problematic, and has happened, and more than once.

PGP

Let’s contrast with PGP. PGP abandons the idea of a Certificate Authority and PKI in general in favor for something called a Web of Trust. When a PGP key is generated with a tool like GPG, they aren’t signed by a known-trustworthy authority like a CA. In that respect, they very much start off like self-signed certificates in PKI. They aren’t trusted until the certificate has been endorsed by one, or multiple, people. These are sometimes done at “key signing parties” where already trusted members of the web will verify the living identity to those with new PGP keys. This scheme is flexible in that it doesn’t rely on a handful of corporations.

Most importantly to many people, it is free. Anyone can participate in this with out monetary requirements or identifications. However getting your PGP key trusted by the Web of Trust can be challenging and due to its flexibility, may not be be immediately actionable.

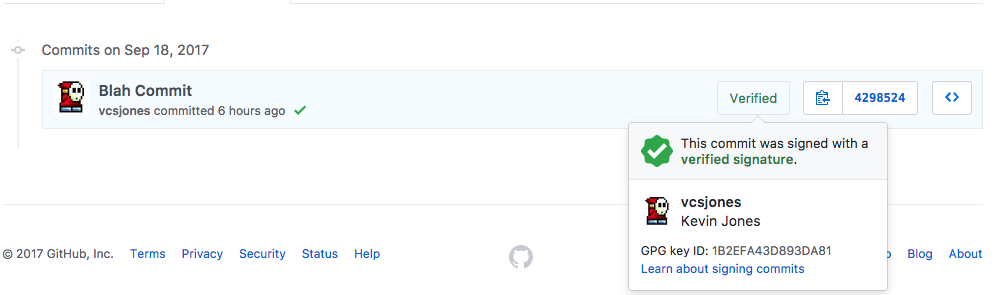

It’s likely that if NuGet did opt to go with PGP, a Web of Trust may not be used at all, but rather to tie the public key of the PGP key to the account in NuGet. GitHub actually does something similar with verified commits.

This, however, has an important distinction from an x509 code signing certificate: the key does not validate that Kevin Jones the person performed the signature. It means that whoever is in control of the vcsjones Github account performed the signature. I could have just as easily created a GitHub account called “Marky Mark” and created a GPG key with the email markymark@example.com.

That may be suitable enough for some people and organizations. Microsoft may be able to state that, “our public key is ABC123” and organizations can explicitly trust ABC123. That would work until there was a re-keying event. Re-keying is a natural and encouraged process. Then organizations would need to find the new key to trust.

This is harder for individuals. Do I put my public key on my website? Does anyone know if vcsjones.dev is really operated by someone named Kevin Jones? What if I don’t have HTTPS on my site - would you trust the key that you found there?

Adopting in to the “web of trust” tries to work around that problems of key distribution. However the website evil32.com puts it succinctly:

Aren’t you suppose to use the Web of Trust to verify the authenticity of keys?

Absolutely! The web of trust is a great mechanism by which to verify keys but it’s complicated. As a result, it is often not used. There are examples of GPG being used without the Web of Trust all over the web.

The Web of Trust is also not without its problems. An interesting aspect of this is since it requires other users to vouch for your key, you are now disclosing your social relationships, possibly because you are friends with the other people used to vouch for the key.

It also has a very large single point of failure. Anyone that is part of the strong set is essentially a CA compared to x509 - a single individual compromised in the strong set could arguably be said to compromise the entire web.

For those reasons, we don’t see the WOT used very often. We don’t see it used in Linux package managers, for example.

Linux, such as Debian’s Aptitude, use their own set of known keys. By default,

a distribution ships with a set of known and trusted keys, almost like a

certificate store. You can add keys yourself using apt-key add, which many

software projects ask you to do! This is not unlike trusting a self signed

certificate. You have to be really sure what key you are adding, and that you

obtained it from a trustworthy location.

PGP doesn’t add much of an advantage to x509 in that respect. You can manually trust an x509 just as much as you can manually trust a PGP key.

It does however mean that the distribution now takes on the responsibilities of a CA - they need to decide which keys they trust, and the package source needs to vet all of the packages included for the signature to have any meaning.

Since PGP has no authority, revoking requires access to the existing private key. If you did something silly like put the private key on a laptop and lose the laptop, and you didn’t have the private key backed up anywhere, guess what? You can’t revoke it without the original private key or a revoke certificate. So now you are responsible for two keys: your own private key and the certificate that can be used to revoke the key. I have seen very little guidance in the way of creating revoke certificates. This isn’t quite as terrible as it sounds, as many would argue that revocation is broken in x509 as well for different reasons.

Tooling

On a more personal matter, I find the tooling around GnuPG to be in rough shape, particularly on Windows. It’s doable on macOS and Linux, and I even have such a case working with a key in hardware.

GPG / PGP has historically struggled with advancements in cryptography and migrating to modern schemes. GPG/PGP is actually quite good at introducing support for new algorithms. For example, the GitHub example above is an ed25519/cv25519 key pair. However migrating to such new algorithms is has been a slow process. PGP keys have no hard-set max validity, so RSA-1024 keys are still quite common. There is little key hygiene going on and people often pick expiration dates of years or decades (why not, most people see expiration as a pain to deal with).

Enterprise

We mustn’t forget the enterprise, who are probably the most interested in how to consume signed packages. Frankly, package signing would serve little purpose if there was no one interested in the verify step - and we can thank the enterprise for that. Though I lack anything concrete, I am willing to bet that enterprises are able to handle x509 better than PGP.

Wrap Up

I don’t want to slam PGP or GnuPG as bad tools - I think they have their time and place. I just don’t think NuGet is the right place. Most people that have interest in PGP have only used it sparingly, or are hard-core fanatics that can often miss the forest for the trees when it comes to usable cryptography.

We do get some value from PGP if we are willing to accept that signatures are not tied to a human being, but rather a NuGet.org account. That means signing is tied to NuGet.org and couldn’t easily be used with a private NuGet server or alternative non-Microsoft server.

To state my opinion plainly, I don’t think PGP works unless Microsoft is willing to take on the responsibility to vet keys, we adopt in to the web of trust, or we accept that signing does not provide identity of the signer. None of these solutions are good in my opinion.